Seeing everything in its duality, we begin to get some dim clues to direction and what it’s all about. It is in these contradictions and their incessant interacting tensions that creativity begins.

— Saul Alinsky, Rules for Radicals

What does it truly mean to be human in a world increasingly shaped by technology? This question is thrown into sharp relief by artificial intelligence. AI challenges us to think about what we value doing ourselves – the creative acts, the intricate tasks – versus the work we’d happily hand off to machines. This deep current about human purpose, creativity, and the meaning of effort is something I’ve navigated throughout my own strange history with computers.

My relationship with technology started out in an odd way. I wasn’t an early adopter; I had a flip phone until I was eleven (this was already around 2016) and my first proper computer was ancient, barely capable by modern standards (think Intel integrated graphics supporting only OpenGL 2.1).

Yet, against the odds, I fell completely, strangely in love with computers.

My first step into programming came through a random CoderDojo book on making websites. I was utterly intrigued. The idea that I could type seemingly random text into Notepad and see something appear in a browser – black text on a white background, yes, but my black text – was nothing short of magic.

This was back when Google Chrome had sharp tabs and Windows 10 was a distant concept. My laptop, a Thinkpad T61, was likely older than me, and internet access was a clunky SIM-card USB dongle. But none of that mattered. I was amazed. This was how people made websites? I had to know more.

Of course, my early journey included classic beginner frustrations – like spending an hour trying to figure out why images wouldn’t load, only to realize I hadn’t actually downloaded the image files. Young me clearly had some conceptual gaps; but the drive remained. I reached the end of the book, stopping only because the final chapter required resources I couldn’t afford (a server, a domain name, FTP access). The itch, however, never quite went away.

Fast-forward a few months. Passing time at my grandmother’s office, I borrowed a small netbook which ran Linux Mint. This marked the beginning of a long spiral – one I’m still not sure is upward or downward.

My initial attempts were clumsy. Trying to run Windows .exe files led to a frustrating afternoon of research and the realization of fundamental incompatibility. But this frustration pushed me to explore. A little C++ here, some Javascript there, diving into Linux configuration.

After a while, I eventually parted ways with that laptop and had to return it to the office. But the seed was planted. Years later, during the pandemic, I returned to Linux on that old machine.

This renewed exploration fostered in me a deep appreciation for minimalism. At this time, I still had a horrible computer. It only had 4GB of RAM and an old CPU. I started looking into the suckless philosophy – software focused on simplicity, clarity, and control. I transitioned to the terminal, abandoned resource-hungry modern applications as much as I could, and developed a disdain for software I saw as bloated and wasteful, ignoring the potential of older hardware.

I loved low-end, suckless, minimalism. It felt pure, efficient, and deeply intuitive. It was immense fun exploring the limits of what I could do with constrained resources, a creative challenge in itself.

Yet, this phase brought its own frustrations. My journey through distros – Pop!OS, Arch, Artix, Alpine, Gentoo, LFS – revealed that going lower often meant more pain. Waiting half a day for Gentoo to compile, only for it to fail? Not fun. LFS, while giving me a lot of experience, was absolutely not viable for everyday use.

I started to hate the rigidity and pain of suckless itself. Spending hours configuring a tiny detail for a marginal gain felt unproductive. The supposed “simplicity” of the terminal dissolved into layers of complex choices: shells, plugins, scripting syntax, keybindings, multiplexers… The pursuit of fundamental control felt paradoxically complicated and exhausting.

New software felt bloated and corporate. Suckless felt dogmatic and painful. No matter how hard I looked, there seemed to be something fundamentally off with the dominant paradigms, both mainstream and niche.

I took a break, settling into a simpler, less configured Linux setup. It was boring, but it was at least functional.

Then, further exploration led me to systems like Plan 9 and OpenBSD. They offered glimpses of alternative philosophies, systems built on different core principles. While they had their own flaws, something about them resonated.

But it was a small, niche project called uxn that truly captivated me. uxn is an imaginary computer designed for constrained environments, with its own assembly-like language, uxntal. I’m not a great programmer, and uxntal felt incredibly archaic and alien. The documentation assumed a level of understanding I didn’t possess. I still struggle with it.

And yet, I am in love with uxn. The parts I do grasp make so much sense in their elegant simplicity. It’s a system built around creative constraints, begging the question: what can you build with so little? How do you create text editors, music, or games on this bare metal system?

uxn felt like pure joy, pure exploration. Programming for the inherent satisfaction of problem-solving within a unique system, not for compliance or corporate mandates. It felt, dare I say, human.

Later, encountering Ben Eater’s videos on building computers from scratch reinforced this fascination with understanding the absolute fundamentals – how do 1s and 0s become computation? (Being broke meant I mostly watched, but the principles stuck).

My journey wasn’t just about using different tools; it was about understanding why they were built that way, and exploring alternative ways of thinking about computing. I loved suckless initially because it offered a recontextualization, a return to roots. I loved uxn because it offered a different root, a unique answer to the challenge of computability. I loved Ben Eater because he showed the foundational why.

But I came to abhor suckless when its philosophy became rigid, attempting to apply old methods everywhere and dismissing anything new as inherently “harmful” or “evil.” This wasn’t exploration; it felt like dogma. It was the negative side of valuing the past – an inability to see value in anything new or different.

The most productive and joyful approach, I found, was not to pick a side – old vs. new, minimal vs. complex – but to look at the tension between them, to understand the different solutions people have created across time and context. This is where the creativity lies, as Alinsky suggested, in the interaction of contradictions.

This brings me, finally, to artificial intelligence. The journey through computing’s past, present, and potential futures, and the inherent tensions within it, provides a crucial lens for viewing the current widespread conversation around AI.

Personally, I’ve been hesitant about AI, partly due to its intense resource usage – a stark contrast to my appreciation for efficiency and constrained systems. The idea of “mushing together huge chunks of data” felt inelegant compared to carefully crafted algorithms.

However, my journey has taught me that value isn’t only in perceived elegance or resource efficiency. A good example is waste management. AI can be applied to waste collection, where optimized routes are made to maximize garbage collection, minimize distance between collection and sorting centers, and avoid traffic. Hypothetically, after using AI for a year or two, the routes generated can be interpreted and analyzed in order to create a replacement algorithm for the AI. This is what I see AI being good for: a tool for analyzing solutions to problems that may be too hard for people to come up with on their own.

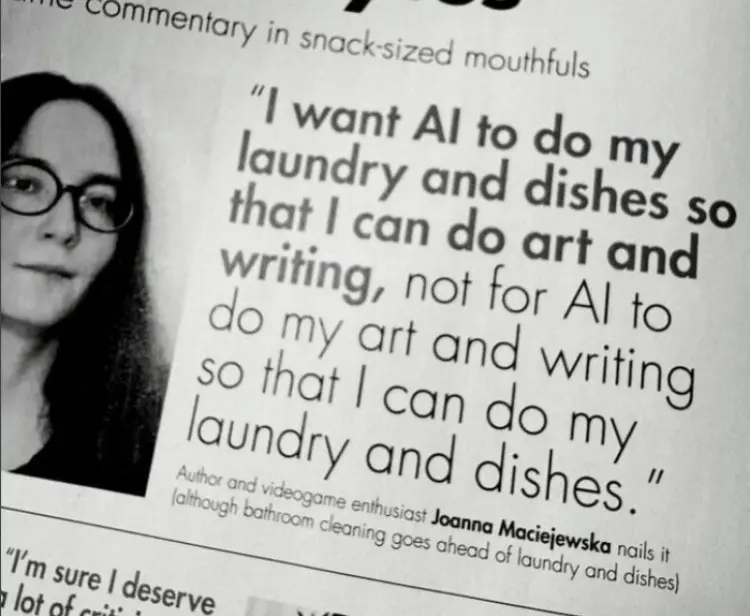

The loudest outcry, though, concerns AI’s impact on creative fields, particularly art and writing. The core conflict here isn’t just about jobs; it’s about legitimacy, authenticity, and what constitutes “art” or “creative work” when generated autonomously from human-made data. It forces us to confront the value we place on human effort and unique expression.

Being an artist, in practical terms, often requires creating work others will value enough to support. Exposure is crucial. But the public has limited time, money, and attention. Their support isn’t guaranteed, regardless of skill or talent.

So, yes, art is a human thing, and its cultural worth is determined by humans. But if AI can replicate outputs that the public values, what then?

This circles back to the question: what does it truly mean to be human? Is it defined by the tasks we perform, the effort we expend, or something deeper?

From what I’ve learned throughout the years, I believe a part of being human is the deep-seated desire to understand our roots, to value history, craft, and the tried-and-true ways of doing things. This explains the appeal of minimalism, of understanding fundamentals. It’s the pull towards the past.

But another equally powerful part of being human is the desire to innovate, to seek comfort, efficiency, and new possibilities. It’s human to want chores done by machines so we have time for other things – creative or otherwise. It’s human to seek out and use tools that make life easier, whether that tool is a hammer, a compiler, or a recommendation algorithm that helps you find a niche artist. It’s the pull towards the future.

These aren’t opposing forces; they are, as Alinsky might say, incessantly interacting tensions. To be human is to embody this duality: the desire to hold onto our past and the desire to move towards the future. They are inextricably linked.

I understand the anger and fear surrounding AI, particularly from artists. Defending one’s livelihood and the value of human skill is valid. But the “blind hatred” and rigid opposition, mirroring the dogma I saw in parts of the tech world, feels unproductive. It reduces a complex issue to an us-vs-them battle, hindering our ability to navigate the tension creatively.

AI itself is not inherently evil; it is a product of human curiosity, ingenuity, and yes, sometimes corporate greed or laziness. It’s a tool developed by thousands of people. Its rise has undoubtedly amplified existing societal problems, like the precariousness of artistic careers in a consumer-driven, intellectual-property-obsessed world. AI didn’t create these problems, but it has made them undeniably apparent. And doesn’t making problems apparent, offering new ways to analyze them, align with the idea of AI as a useful tool?

My frustration is further amplified when I see the online discourse devolve into echo chambers, snarky dismissals, and meme-based arguments presenting one side as angels and the other as villains- the brave poets against the evil watchmakers, or the wise singularitarians against the naive masses. It’s a stark example of humans struggling to grapple with a complex duality, retreating into rigid camps instead of exploring the nuanced space in between.

But perhaps, in a strange way, this too is fundamentally human. This struggle with contradictions, this desire for simple answers in a complex world, this tension between valuing the old and embracing the new – maybe that’s precisely what it means to be human.